Many mock paint by number paintings, saying it’s-not-art-it’s-conformism. “This,” they say, “is not art.” It’s kitsch at its worst, and at its best, it’s a hobby. We collectors disagree. Maybe it’s just ‘cuz we love our paint by number paintings; but maybe it’s because we know things that you mockers don’t.

Many mock paint by number paintings, saying it’s-not-art-it’s-conformism. “This,” they say, “is not art.” It’s kitsch at its worst, and at its best, it’s a hobby. We collectors disagree. Maybe it’s just ‘cuz we love our paint by number paintings; but maybe it’s because we know things that you mockers don’t.

Today, we begin with the history…

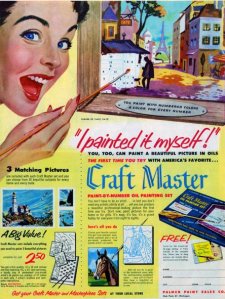

The Palmer Paint Company (Detroit, Michigan) introduced the first paint-by-number kits at the New York Toy Show in 1951, creating Craft Master as its premium line of PBN.

Some might say, “And the rest is history”. But I’m not that short-winded; nor was the story so neat and tidy as to stay within the lines.

The story begins in 1949 when Dan Robbins was working as a package designer for Max Klein at Palmer Paint Company in Detroit, Michigan. Robbins, inspired by childhood memories of coloring & painting, as well as the story of how Michelangelo assigned pre-numbered sections of his famous ceiling to his students to paint, pitches the idea for paintings created by applying paint to color-coded canvases to his boss. Klein resists at first, but eventually, he gives the idea a try.

Rumors suggest that Klein was approached by two employees of the Picture Craft Company of Decatur, Illinois, a company already producing similar art sets consisting of a rolled canvas and glass jars containing paint, though they were “mystery” pictures, where the painter only discovered what they were painting only by applying the appointed colors. Picture Craft Co. had been selling the kits to the military through mail order but wanted Palmer Paint to create both a greater quantity of the sets and a broader national market for them. As the story goes, Klein agrees, starts production, but Picture Craft doesn’t produce the money for the goods and Palmer Paint Co. has to market the sets themselves to get rid of the stock, leaving an opening to go forward with Robbins’ ideas.

Robbins’ first prototype was Abstract No. 1, an impressionist still life painted with tempera colors on cardboard. Klein thought it was not only not marketable, but ugly too. He sent Robbins back with instructions for better designs and the first Craft Master set was “The Fishermen”. It included a canvas stamped with the numbered outline of the scene, gel caps of oil paint, and a palette.

Robbins’ first prototype was Abstract No. 1, an impressionist still life painted with tempera colors on cardboard. Klein thought it was not only not marketable, but ugly too. He sent Robbins back with instructions for better designs and the first Craft Master set was “The Fishermen”. It included a canvas stamped with the numbered outline of the scene, gel caps of oil paint, and a palette.

But still selling the sets wasn’t easy.

In the preface to What Ever Happened To Paint-By-Numbers?, Dan Robbins writes:

Most people think paint-by-numbers was an immediate success. Not true! In the beginning we couldn’t give our sets away. It took almost two years to get our paint-by-number business off the ground. When we finally did, it took off like a rocket. All we could do was hang on for dear life.

If you think the troubles of the early years were comprised of resistance to the concept of such paintings as “art”, let me hip you to some facts.

If you think the troubles of the early years were comprised of resistance to the concept of such paintings as “art”, let me hip you to some facts.

First, the matter of paint by number paintings being art — or, rather, not being art — wasn’t really an issue in the 50′s. Recreation specialists & home economists had begun to speak of hobbies as more than a way to beat the unemployed Depression-era-nothing-to-do-blues, more than a way to improve morale, but as “the fifth freedom,” along with freedom of speech and worship and freedom from want and fear. The prevailing wisdom of the postwar period was that creative hobbies enhanced life and made it worth living, prompting popular celebrities like Frank Sinatra & Dinah Shore to paint as a pastime. With “Sunday painters” like President Eisenhower and Winston Churchill, even the military had adopted this mindset, setting up hobby craft shops the Pacific Theater and opening the first hobby craft shop at the Alameda Naval Air Station in California — which is why Picture Craft was selling kits via mail order to the military.

Sure, there was some initial resistance to a new idea, at least from store buyers; but the first real problem with selling paint by numbers lay with the Palmer Paint Company itself, thwarting its own sales.

Sure, there was some initial resistance to a new idea, at least from store buyers; but the first real problem with selling paint by numbers lay with the Palmer Paint Company itself, thwarting its own sales.

Craft Master’s Klein began by cut a deal with his golf buddies, who were buyers at Kresge (K-Mart), to stock the kits. But the first test order was botched because in their haste to produce the kits, Palmer Paint Co. had mixed-up the paint color palettes so that Kit A had Kit B’s colors, etc. Kresge had to take back the kits & refund the customers. With all the complaints Kresge told Klein to forget the deal. That news got around and orders were slim-to-none.

In November of 1950, Klein convinced the Macy’s toy buyer to let Palmer Paint demonstrate the Craft Master kits in their department store during the New York Toy Show. Palmer Paint promised Macy’s that the department store would only have to pay for the sets sold and that all unsold sets would be taken back — and Palmer Paint would pay for an ad in the New York Times announcing that Craft Master sets were available at Macy’s. Macy’s agreed. But Palmer Paint wouldn’t leave it at that. In OUTRÉ Magazine Robbins said:

We knew that, after placing the ad, setting up a demonstration and display, we would surely sell some sets, but we left nothing to chance. We decided to guarantee ourselves that, one way or another. Macy’s would be sold-out by the end of the Toy Show. Max gave each of our two New York reps $250, and instructed them to give it out to friends, relatives, neighbors, anyone who would be willing to come into Macy’s and purchase one of our Craft Master sets. It doesn’t exactly sound kosher, but we knew Paint-By-Numbers was a winner, and wanted to do whatever it took to convince Macy’s and everybody else that it was.

Kosher or not, the Macy’s event combined with the New York Toy Show itself gave Craft Master and paint by number kits the push needed. And in 1952, an amateur painter in San Francisco entered and won third place at an art competition with one of Craft Master’s kits, Robbins’ Abstract #1 (yup, the first rejected prototype). Both the press and the public had a field day noting how judges could not tell the difference between a paint by number work and Modern Art — an art style in its hey-day, but one many people at the time were confused by &/or fed up with.

Kosher or not, the Macy’s event combined with the New York Toy Show itself gave Craft Master and paint by number kits the push needed. And in 1952, an amateur painter in San Francisco entered and won third place at an art competition with one of Craft Master’s kits, Robbins’ Abstract #1 (yup, the first rejected prototype). Both the press and the public had a field day noting how judges could not tell the difference between a paint by number work and Modern Art — an art style in its hey-day, but one many people at the time were confused by &/or fed up with.

This was the tipping point for paint by numbers. They became so popular that The White House even hung paint-by-number paintings by J. Edgar Hoover, Nelson Rockefeller and others in a West Wing corridor along with other artists’ original works. In 1953, Picture Craft was out of business, and Craft Master was “It” with a capital “I”.

But while paint by numbers were a hot new trend, it was also a new business. And Craft Master was having traditional business problems, such as properly pricing their kits for a profit. John Robbins explains to John Rossi in OUTRÉ Magazine issue 17:

But while paint by numbers were a hot new trend, it was also a new business. And Craft Master was having traditional business problems, such as properly pricing their kits for a profit. John Robbins explains to John Rossi in OUTRÉ Magazine issue 17:

The first time we attempted this, we started with “Paint-A-Star.” One of our reps knew the agent who represented Dinah Shore, Liberace, Bob Hope, Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. My assignment was to do Liberace. I must have painted Liberace 20 times, and every time I sent it to him for his approval, he always found problems with his hair. It was too long, it was too dark, it was too gray.

Anyway, Max came to me one day and said, “Dan, you tell me – can we do this or not?” …I told him I thought we could. …We also came up with a pretty clever way to present the idea to the buyers.

First, we secretly acquired photos of all the buyers from the various department stores. We converted the photos into numbered canvases, included paint, brushes, complete instructions – all packaged into prototype packaging – just as the product would appear in the retail stores. We not only presented each of the seven or eight major buyers with their very own Paint-By-Numbers kit, but each of them also received a finished portrait, beautifully framed, with their name inscribed on a gold metal plate. That’s a presentation! Ultimately, the personalized portrait failure could be blamed on the simple fact that we couldn’t turn a profit on the suggested retail price of $19.95. We had underestimated the cost of hand labor in converting the original photos to a numbered outline. We probably sold two or three thousand at $19.95 – and we lost our ass! We couldn’t make any money on it, in spite of the fact that Life magazine picked it up, The Wall Street Journal, we had all kinds of publicity. It was a good idea, but it bombed.

As far as the consumer went, PBN was a hit. By 1954, Palmer had sold some twelve million kits, was producing 50,000 kits per day, and had as many as 30 competitors making their own PBN sets.

No wonder we all remember paint by number paintings.

As I said, originally the Craft Master kits were printed on rolled canvas, but when competition entered the market with kits consisting of the now-familiar boards with light-blue outlines and using acrylics rather than oils, Craft Master followed suit. (Naturally, these canvas paint by numbers are highly sought after and more expensive.)

The year given for this change is 1955, which is the same year the company, which had filed for bankruptcy, was purchased by the Donofrio brothers of Toledo, Ohio, whose company had been supplying the containers for Palmer paints and the Craft Master kits. While the kits were now selling well, the early problems combined with the pricing issues had put the company Craft Master in a financial hole; naturally the Donofrio brothers wouldn’t want to lose their own paint container sales, so they bought the company.

A few years later, General Mills (who had been busy buying Parker Brothers, MPC Model Kits, Play-Doh, Lionel Trains, and Kenner in the U.S. as well as international toy companies) bought Craft Master, placing it under its Fundimensions line.

A few years later, General Mills (who had been busy buying Parker Brothers, MPC Model Kits, Play-Doh, Lionel Trains, and Kenner in the U.S. as well as international toy companies) bought Craft Master, placing it under its Fundimensions line.

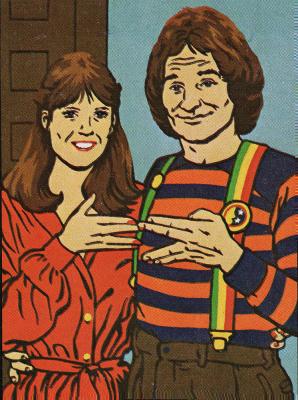

General Mills even came back to Robbins with an idea to improve the personal paint by number portraits:

…and they said to me, “Dan, the age of computers is here. What you couldn’t do then, we can now do with computers. Your assignment, should you choose to accept it, is to head this group.” The group was ITEK Corporation, a group that was doing work for the space shuttle and had all the technology in the world. Their language was so technical, I couldn’t understand it. But the final product was a series of tiny squares with printed numbers corresponding to a particular color, instead of a picture that resembles what the final picture might look like. Suffice it to say that, even though the finished painting looked great, it was much more difficult and complicated to paint than the Paint-By-Numbers everybody had been used to.

The General Mills toy division was spun-off as Kenner Parker Toys Inc. (1985), which was then purchased by the Tonka Corporation (1987), which was purchased by Hasbro (1991). But Vicky Edwards Gehrt in a 1995 Chicago Tribune piece wrote that Craft Master ended up with International Assemblix, now called Craft House. (Craft House is currently run by Chartpak, Inc., and doesn’t use the Craft Master name, but rather the Original Paint-By-Number® slogan.)